As Bob Ross, the American painter and host of The Joy of Painting used to say, “We don’t make mistakes, we just have happy accidents.” Apparently, painters aren’t the only ones can who turn a mistake into something amazing. Throughout history, some of the best scientific discoveries were the result of something gone wrong in the laboratory.

Matches, 1826

English pharmacist John Walker was working in his laboratory and noticed a dried lump of material on the end of the stick he was using to stir a chemical mixture. When he tried to scrape it off, it sparked and caught fire. Walker was able to recreate the lump, which was a mixture of antimony sulfide and potassium chlorate, and attached it to small strips of cardboard, which he sold in his pharmacy as “Friction Lights.” He eventually replaced the cardboard with hand-cut wooden splints and placed them in a box with a piece of sandpaper on the outside for striking.

Walker refused to patent his accidental laboratory discovery because he considered it a product that could benefit all of mankind. Needless to say, many others copied his idea, and Walker stopped making his version.

Mauve, 1856

The color mauve may not be the most exciting accidental laboratory discovery in this list, but when you consider it came about because a teenage chemist was looking for a treatment for malaria, the story gets a whole lot more interesting.

An eighteen-year-old chemical analysis student, William Henry Perkin, studying at the Royal College of London was trying to synthesize quinine in the laboratory, a known treatment for malaria, from coal tar. His attempts were not successful, and the experiment left behind a solid, blackish-colored residue in his beaker. While trying to clean up his mess with alcohol, Perkin noticed the material had a purplish hue. Perkin had created the world’s first synthetic dye without intending to do so.

Insulin, late 1880s

Two doctors in the late 1880s were trying to understand the role of the pancreas in digestion. To research and test a theory, they removed the pancreas from a dog. Weeks later they noticed flies were attracted to the dog’s urine. When they tested it in their laboratory, they found it had higher sugar content than normal. They had accidentally given the dog what we now know as diabetes.

Without these doctors unintentionally discovering the part the pancreas plays, Dr. Frederick Banting may have never been able to isolate the secretions from the islet cells and produce insulin, a treatment for diabetes that had a huge impact on the healthcare field.

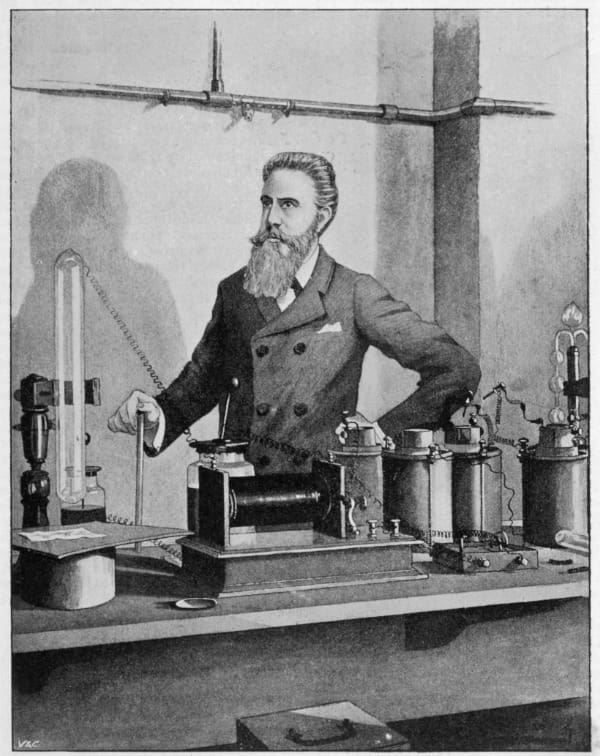

X-rays, 1895

In his laboratory in Wurzburg, Germany, physicist Wilhelm Conrad Rontgen was conducting an experiment to see if cathode rays could pass through glass. He noticed an odd glow coming from a screen coated with a chemical called barium platinocyanide across the room. He attempted to disperse the glow with his hand and discovered the glow projected an image of his bones on the screen.

Rontgen replaced the screen with a photographic plate and created the x-ray, one of the early medical devices. For his accidental laboratory discovery of radiation, he won the first-ever Nobel Prize in physics in 1901.

Plastic, 1907

A Belgian chemist, Leo Baekeland, was on a quest to discover a synthetic material to replace shellac, an organic resin secreted by female lac bugs. Baekeland combined formaldehyde and phenol, a waste product of coal, and then heated it. Rather than creating a glaze-like substance resembling shellac, he created a polymer that was unique, as it did not melt under stress and heat.

Now, the lightweight, moldable, thermosetting plastic is used in manufacturing to make just about everything from household appliances to jewelry. In a 1924 article, Time magazine called it a “material of a thousand uses,” and they couldn’t have been more right.

Safety glass, 1909

We can thank the discovery of safety glass to the unsteady hands of French chemist Edouard Benedictus. While in his laboratory, Benedictus dropped a glass flask. The flask broke but did not shatter, due to the interior coating of plastic cellulose nitrate, or liquid plastic. Benedictus realized that if he bonded a layer of celluloid between two layers of glass, he could prevent automobile windshields from shattering during an accident.

The unintentional laboratory discovery was initially dismissed by the automobile industry due to its high cost, but it became useful in World War I when it was used for the eyepieces of gas masks. The automakers started making windshields of safety glass in 1927.

Penicillin, 1928

Alexander Fleming, a Scottish physician, bacteriologist, and microbiologist, was conducting experiments in his laboratory in London with the influenza virus and investigating staphylococci, commonly known as staph. He decided to leave his work and embark on a two-week vacation. When he returned, Fleming discovered a fungus growing on a culture he had left in the lab. The fungus had killed off all the surrounding bacteria in the culture.

That unexpected laboratory discovery was what we now know to be penicillin, one of the first pharmaceuticals proven against bacterial infections, and still prescribed today for meningitis, pneumonia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and urinary tract infections, as well as many more. And we have Fleming’s untidy laboratory to thank for it.

Teflon, 1938

While working for what is now known as DuPont and experimenting with ways to create new chlorofluorocarbon refrigerants that were non-toxic and non-flammable, scientist Roy Plunkett opened one of his sample containers and found that his experimental gas was gone. Instead, he discovered a white powder that he tested and learned was resistant to extreme heat and chemicals.

The first application was on the Manhattan Project, where its corrosion resistance proved useful as a coating on valves and seals in the pipes holding highly reactive uranium hexafluoride. It wasn’t until the 1960s that Teflon would be used to create non-stick cookware.

Super glue, 1942

While part of Eastman-Kodak’s chemical research team was trying to make clear plastic gunsights for weapons during World War II out of cyanoacrylates, an American, Dr. Harry Coover, accidentally created the uniquely powerful bonding agent that we know today as super glue.

While working with the chemicals, Coover discovered that they were extremely sticky, and this property made them very difficult to work with. Moisture caused the chemicals to polymerize and bonding would occur in virtually every testing instance. Coover and his team rejected cyanoacrylates as a feasible option for the gunsights and moved on with their research. Coover re-discovered the potential for cyanoacrylates six years later and received patent number 2,768,109 for his “Alcohol-Catalyzed Cyanoacrylate Adhesive Compositions/Superglue.”

Viagra, 1992

Scientists working for the pharmaceutical company Pfizer in the United Kingdom were trying to develop a pill to relax blood vessels around the heart, improve blood flow, and provide relief to those who suffered from chest pains, more specifically, angina pectoris. The pill failed at its primary purpose, but male test subjects reported an interesting side effect.

The pill improved blood flow in the arteries within the penis. Today, we know Viagra as the multibillion-dollar erectile dysfunction drug that was commercially released in 1998.

Where would we be without accidental laboratory discoveries?

Miscalculations and failed experiments usually prove very costly for scientists and research teams, having wasted time, money, and effort on an unsuccessful project. However, not every failure is a waste. Without accidentally discovering a new scientific principle, chemical compound, or adverse reaction, some of the greatest achievements in cures for disease, inventions, or scientific innovations would have never happened.

Yes, these scientists noted above may have gotten lucky and stumbled on something they didn’t expect. But it took their curiosity, brilliant minds, and devotion to science to figure out a way to turn a negative into a positive.

Contact Us

One of the biggest differentiators between LabLynx and other LIMS vendors is…us! We are all chemists, biologists, laboratory managers, lab quality officers, biomedical and process engineers…most of our staff used to be customers, and decided to join us! To read more articles, brochures, books, of FAQs, visit our Resources page! We also have more specific information on our services, products, and industries served!

We at LabLynx would very much love to schedule an initial meeting and further communications to learn about you and your lab. We look forward to working collaboratively with you to establish a shared vision of how our LIMS solution can be the right fit for you. Please contact us at www.lablynx.com/contact-us or [email protected] and we will set up an initial meeting!